Scientists have uncovered how a deadly hospital pathogen, Acinetobacter baumannii, evolves to resist last-line antibiotics, insights that could pave the way for more precise and personalized treatments. The findings, published in Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy on October 29, 2025, come from researchers at the Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute and their collaborators at Roche Pharmaceuticals.

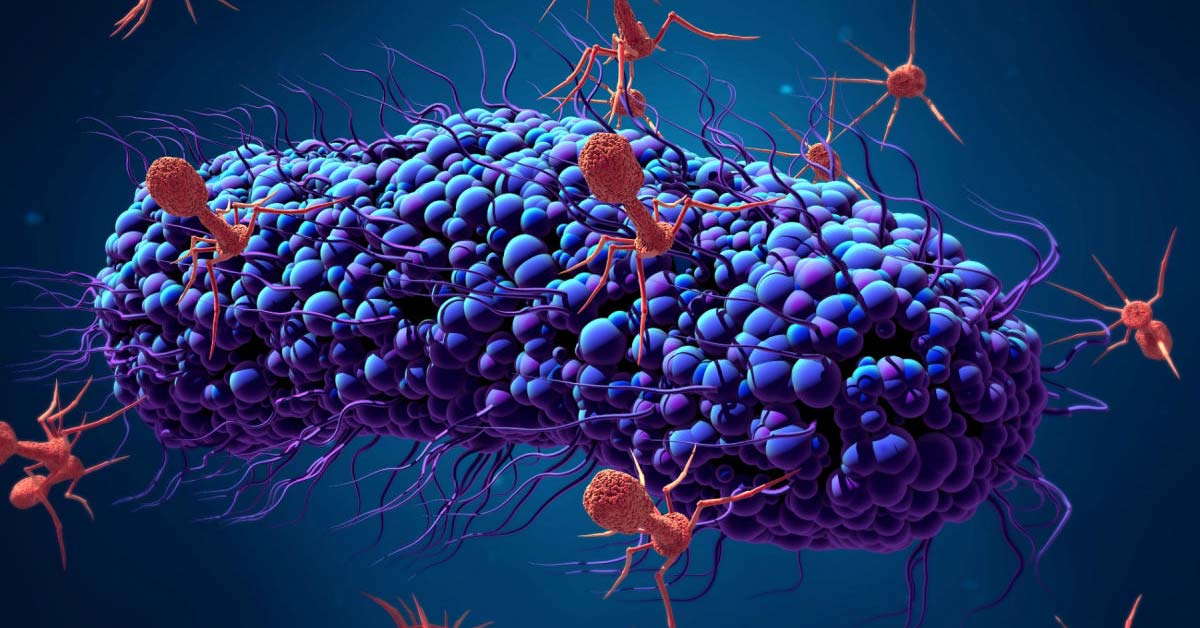

Acinetobacter baumannii is a major cause of hospital-acquired infections and is known for its remarkable ability to survive harsh environments and evade standard drugs. In the United States alone, more than one in 100 hospitalized patients is treated for infections caused by this highly adaptive bacterium. Because of its growing resistance, physicians have been forced to rely on less commonly used antibiotics such as tigecycline and colistin, the last options for many patients.

To better understand how this pathogen develops resistance, the research team used a device called a morbidostat, which continuously exposes bacteria to increasing doses of antibiotics. The setup acts as an “evolution machine,” allowing scientists to observe bacterial adaptation in real time. By pairing this method with genomic sequencing, the team mapped the full range of possible genetic mutations that enable A. baumannii to survive antibiotic pressure.

“This is a deadly pathogen that is notorious for its resistance to traditional drugs,” said Dr. Andrei Osterman, senior author of the study and professor at Sanford Burnham Prebys. “Our goal was to capture the complete picture of how these bacteria evolve resistance, which could ultimately guide more targeted treatments.”

The study revealed that tigecycline resistance often arises from mutations affecting efflux pumps, systems bacteria use to expel toxic compounds, including antibiotics. In contrast, resistance to colistin was linked to mutations in enzymes that modify the bacterial cell wall, preventing the drug from reaching its target.

By comparing these experimentally evolved strains with over 10,000 publicly available bacterial genomes, the researchers confirmed that similar mutations are already present in clinical isolates worldwide. This comprehensive genetic map could help clinicians predict which antibiotics are most likely to work against a specific infection, based on its genetic profile.

“A serious problem occurs when patients are treated by trial and error,” explained Osterman. “The data we are accumulating could allow doctors to order a quick sequencing test and select an antibiotic the bacteria are least likely to resist.”

The research highlights a shift toward genomics-guided medicine, where rapid DNA testing can inform treatment choices before resistance becomes deadly. The team hopes their approach will reduce treatment failures and slow the global spread of antibiotic-resistant infections.