New research suggests that genetics may unexpectedly influence health, not only through an individual’s own DNA, but also through the genes of the people they live with. A large study conducted on laboratory rats reveals that gut bacteria are shaped not just by personal genetics, diet, or environment, but also by the genetic makeup of social partners sharing the same living space.

The study, published in Nature Communications and led by scientists at the Center for Genomic Regulation in Barcelona, analyzed gut microbiome data from more than 4,000 genetically diverse rats. The findings challenge the traditional view that genetic effects act only within an individual’s body. Instead, they show that genetic influences can “spill over” from one individual to another through the social sharing of microbes.

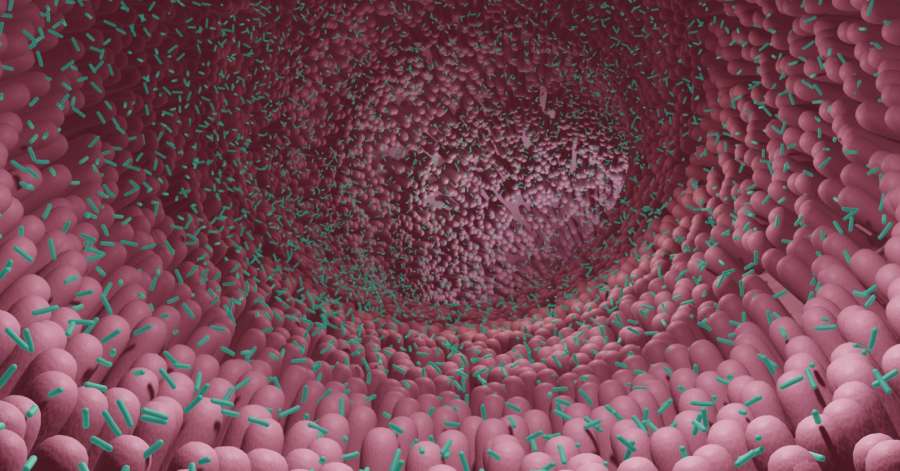

Gut microbiota consist of trillions of microorganisms that play critical roles in digestion, immune regulation, metabolism, and overall health. While diet and medication are known to strongly shape these microbial communities, identifying direct genetic effects has been difficult, especially in humans, where lifestyle and environmental factors overlap. To overcome these challenges, researchers used rats raised under controlled conditions with standardized diets and housing.

The results showed that certain genes promote the growth of specific gut bacteria, which can then spread to cage mates through close contact. One of the strongest genetic associations involved the gene St6galnac1, which alters sugar molecules in the gut’s mucus lining. Rats carrying specific versions of this gene had higher levels of Paraprevotella, a bacterium that feeds on these sugars. Because microbes can move between individuals, this bacterial advantage extended to rats sharing the same living environment.

Two additional genetic regions were also identified. One was linked to mucin-producing genes that help form the gut’s protective mucus barrier and influenced bacteria from the Firmicutes group. Another involved the Pip gene, which produces antibacterial molecules and affects bacteria from the Muribaculaceae family. Importantly, these genetic effects were consistent across four independent rat populations housed at different research facilities, strengthening the reliability of the findings.

The researchers used advanced computational models to separate the effects of an individual’s own genes from those of their social partners. When these indirect genetic effects were included, the estimated genetic influence on certain gut bacteria increased by four to eight times. This suggests that previous studies may have underestimated how strongly genetics shapes the microbiome.

Although the study was conducted in rats, the findings may have important implications for humans. The rat gene St6galnac1 is functionally related to the human gene ST6GAL1, which has already been linked to gut bacteria in earlier research. If similar processes occur in people, genetic influences on health, such as susceptibility to infections, immune disorders, or metabolic diseases, may extend beyond individuals to those living around them.

Overall, the study highlights a new dimension of genetics, showing that genes can affect others indirectly through shared microbes. This insight could reshape how scientists understand heredity, disease risk, and the complex relationship between genetics, social interaction, and health.